In the early 1930s, along with the greatest depression this nation ever experienced, came an equally unparalleled ecological disaster known as the Dust Bowl. Following a severe and sustained drought in the Great Plains, the region’s soil began to erode and blow away, creating huge black dust storms that blotted out the sun and swallowed the countryside. Thousands of “dust refugees” left the black fog to seek better lives.

These storms soon stretched across the nation. They reached south to Texas and east to New York. In these years before air conditioning, dust sifted into the White House and onto the desk of President Franklin Roosevelt. On Capitol Hill, while testifying about the erosion problem, soil scientist Hugh Hammond Bennett threw back the curtains to reveal a sky blackened by dust. Congress unanimously passed legislation declaring soil and water conservation a national policy and priority. Since about three-fourths of the continental United States is privately owned, Congress realized that only active, voluntary support from landowners would guarantee the success of conservation work on private land.

In 1937, President Roosevelt wrote the governors of all the states recommending legislation that would allow local landowners to form soil conservation districts. South Carolina’s Governor, Olin D. Johnston signed the S.C. Conservation Districts Law on April 17, 1937. This law established the working partnership between the United States Secretary of Agriculture, the State of South Carolina, the S.C. Department of Natural Resources, and each conservation district in South Carolina.

Over the more than seventy five years of the South Carolina Conservation Districts’ existence, the goals remain the same: to install best management practices to stop soil erosion and maintain good water quality and to educate the public about the importance of both.

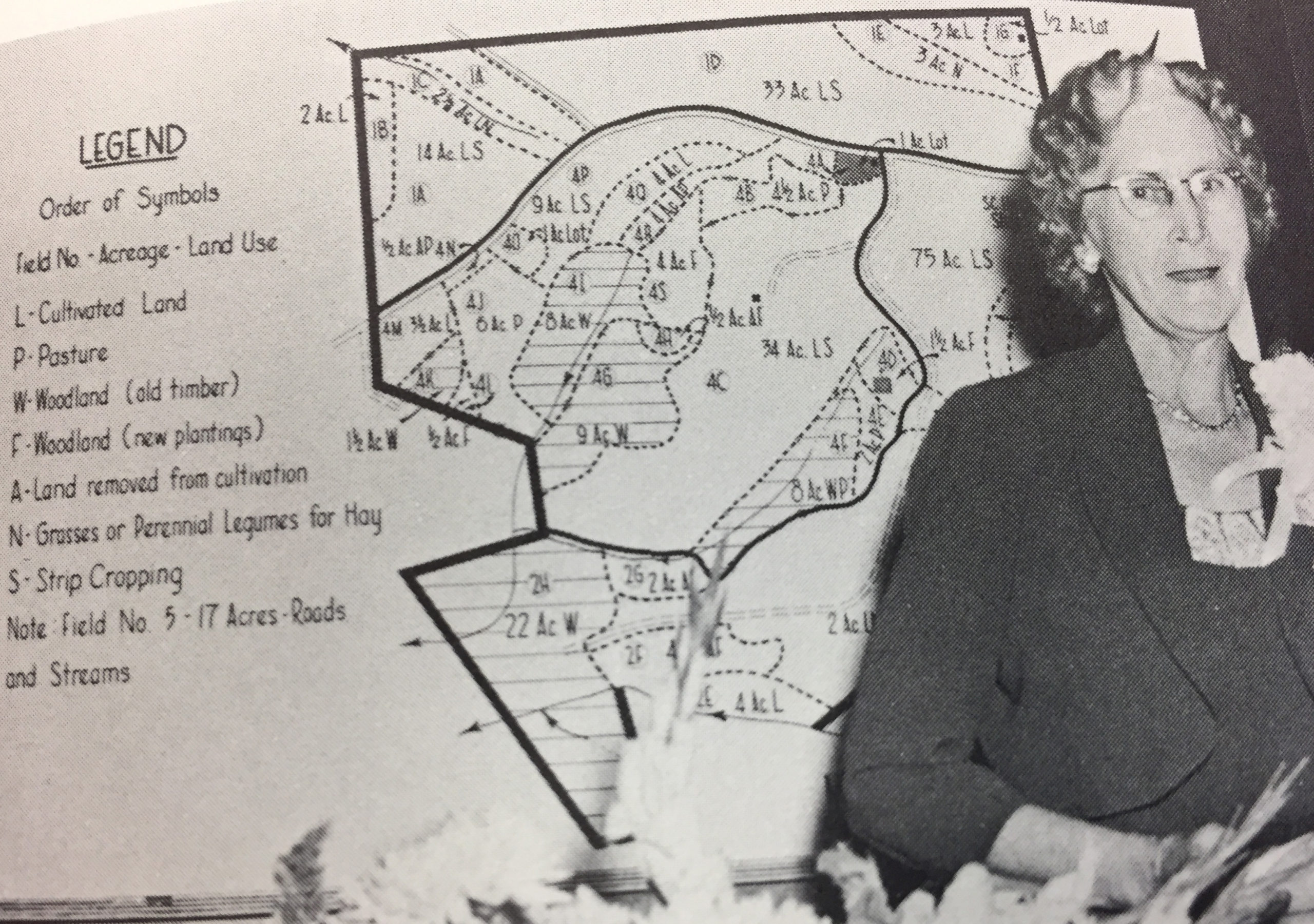

First Conservation Plan in the United States

With a five million dollar budget, the federal Soil Erosion Service set up demonstration sites in strategic locations throughout the United States. One of the first demonstration sites in the United States covered the South Tyger River Watershed, located in Greenville and Spartanburg counties. The project began on December 18, 1933 at the J.L. Berry farm, located near Poplar Springs in Spartanburg County where a gully, large enough to swallow a vehicle, was repaired.

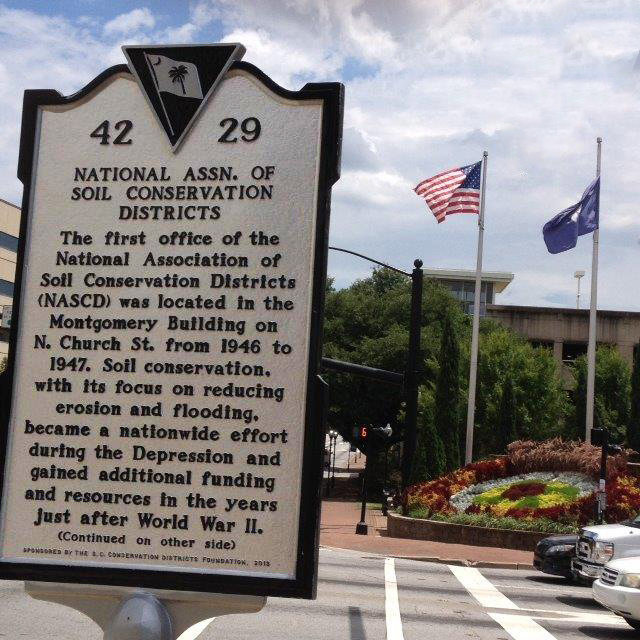

The first office of the National Association of Conservation Districts in Spartanburg recognized with an official historical marker.

The first office of the National Association of Conservation Districts in Spartanburg has been recognized with an official historical marker. The marker is on the corner of West St. John and North Church streets across from the Montgomery Building, which housed the association’s offices from 1946-1947. E.C. McArthur of Gaffney was the association’s first president. The national office remained in the Montgomery Building until McArthur’s death in September 1947.